By Shranya Gambhir:

My earliest memories of reading include sitting with my mother, reading Enid Blyton books and practising phonetics. I learnt how to speak and comprehend a foreign language through stories that were culturally alien to me, through illustrations that did not look like anyone or anything around me. I recall reading LadyBird Education’s The Little Magic Porridge Potalmost every night and wondering what porridge was and what it must look like. While these books did the task of teaching me how to read and understand, rarely did they ever make me want to read. It wasn’t until one of my teachers introduced me to Sandhya Rao’s Ekki Dokki, an Indian folktale about two sisters, that I began to view reading as an enjoyable solitary activity, separate from the dedicated reading hour at school.

Over the next few years, I developed a deeply fulfilling reading habit that was simultaneously grounded in my immediate reality and also a window to people and cultures I’d never known of before. In a world that is becoming increasingly divisive, I believe that cultivating empathy and helping people question their own prejudices and biases is more important than ever before. Books play a fundamental role in providing an insight into the world; they hold up a mirror to society and reflect the reader’s life, but also, they act as windows through which the reader can learn about the lives of other people.

The need for socially conscious and inclusive literature starts young. Children’s books are one of the most effective and practical tools for initiating critical conversations. Children need to see themselves in the books they read, they need to see images that represent their lives, celebrate their experiences and let them know that they are not alone. Seeing oneself represented in literature encourages the reader to feel a sense of involvement and enables them to immerse themselves in the stories they read. Crucially, it produces the feeling of agency in the reader, which includes the agency to approach others with empathy.

Over the last few months, I have been part of the organising team of the Belongg Online Literature Festival, a four-day event that seeks to bring together authors and speakers for sessions on gender, sexuality, race, caste, religion and disability. While planning the program for the festival, we have tried to bring together people who recognise the crisis of children’s literature and are working tirelessly to bridge the gaps. The Festival aims to amplify voices that dare to introduce books that break the boundaries of imagination and social relation.

Children’s books and value of conscious representation

Everyone agrees that all children deserve to read stories that make them feel seen – stories that make them feel empowered on the one hand and, on the other, enable them to understand cultures and possibilities that previously seemed alien or impossible. Despite such deeply held beliefs and significant research that highlights the value of conscious representation, the landscape of children’s literature presents a troubling reality.

Mango & Marigold Press, an independent publishing company based in Boston, conducted research which found that there are five times as many books about trucks and two times as many books about bunnies than there are any books about children of colour. In a similar vein, of the 3,200 children’s books published in the US in 2018, according to Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin, just 1% featured indigenous characters, only 7% depicted Asian characters, and only 10% represented Black characters. Further, data published by the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education shows that of the 9,115 children’s books published in the UK in 2017, only 4% featured children of colour as central characters. In addition to this glaring gap in numbers, stories that do feature characters of colour most often represent them as background characters, reinforce stereotypes or, worse, are inappropriate and insensitive.

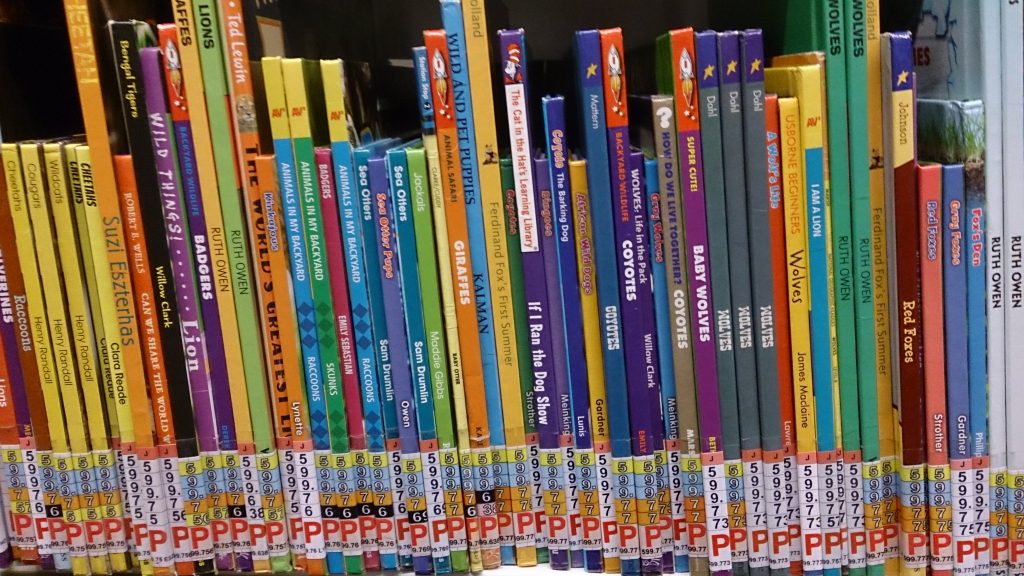

Stories that feature characters of colour most often represent them as background characters that reinforce stereotypes. Photo: Flickr/Caroline Ramsden CC BY SA 2.0

Closer to home, Shubha Viswanath, publishing director of Karadi Tales, an independent publishing house in Chennai, observes in an article for The Hindu that while India is producing quality content in children’s literature, written primarily in English, the genre is still very small and lacks formal recognition. India is yet to give children’s literature written in regional languages their due, and such books remain largely absent from the market. Shubha noted that across a range of literature festivals in India, panels on children’s literature are often missing. Further, the Indian market is fixated on retelling and consuming traditional stories from the past, consuming books that reinstate ‘good morals’ and don’t necessarily ask difficult questions of contemporary relevance.

Radhika Menon, founder of Tulika Publishers, while presenting at a conference organised by the National Book Trust, highlighted the lopsided exchange of children’s books between the West and the East leading to a dominance of Western voices and stereotypes in the children’s literature of the East. She stressed on the importance of a more representative exchange of books in the world as well as between different parts of India.

Fail to cultivate inclusive socieites

It is no surprise, then, that our children grow up to be adults who are threatened by difference and, more generally, we fail to cultivate inclusive societies globally. In a world that is being increasingly divided along lines of identity, we must radically reassess representation in literature overall and in children’s literature in particular. The value of this undertaking cannot be overstated. Reading, I believe, takes us closest to experiencing another person’s lived reality, allowing readers to be self-reflexive and critical of their prejudices and biases against ‘the Other.’ This being the case, it is our responsibility to ensure that each child has access to inclusive stories.

The Belongg Online Literature Festival hopes to provide a platform to publishers, authors, illustrators, and translators that recognise this vital need. We invite you to get engaged!

You can read more about the Festival and book your passes at www.belongglitfest.com. You can also read more about Belongg here.

This story was first published on The Wire.

Recent Posts

- No Child’s Play: A Case for Diversity in Children’s Literature

- 7 Must-read books on the intersection of identity and mental health

- 5 Books that Address Social Justice and Prejudice in Museum Spaces

- 7 Interesting Books That Reflected Diversity in 2019

- 3 Female Characters In Classic Literature Who Taught Me About Feminism Early On

Recent Comments